Ready to proof -- Clare 7-8-22

KJ proofed on 7/15 and sent correction to Clare

Revised on 7/15

Ready for author

Video: pigphoto / Creatas Video+ / Getty Images Plus, via Getty Images.

Using Smart Marine Coatings

to Help with the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index

By Marciel Gaier, Chief Technical Officer; Ryan Ingham, Junior Chemical Engineer; Ilia Rodionov, Lead Product Formulations and R&D; and Mo Algermozi, Chief Executive Officer, Graphite Innovation and Technologies Inc., Dartmouth, NS, Canada

With the Greenhouse Gas Strategy moving towards 2050, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has set the goal to reduce carbon intensity by 40% within the next decade up to 2030 and by 50% in total (70% intensity) up to 2050. The Greenhouse Gas Strategy was approved by the IMO in 2018. The reduction rates are related to the baseline of 2008. Short-, mid- and long-term measures are distinguished to achieve the goal. Short-term measures are meant to be set into force by 2023. The requirements will enter into force January 1 of that year. The Energy Efficiency Existing Index (EEXI) is a method for regulating the fuel efficiency of ships, and is applicable for all vessels above 400 GT falling under MARPOL Annex VI.1

The roughness of a hull is known to affect a ship’s hydrodynamic performance and tends to increase due to the age of the ship, improper paint application, coatings’ wear-off and biofouling. An increase in hull roughness leads to an increase in a vessel’s fuel consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This phenomenon is becoming a greater issue for ships as the pressure to implement energy efficiency measures is ever-increasing. One example is the EEXI and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), which will be actioned by the IMO on January 1st, 2023.1 These two measures force ship owners to reduce the operational carbon intensity of their marine assets via engine power limitation or energy-saving devices.1

Foul-Release Coatings as Energy-Saving Devices

One example of an energy-saving device would be to employ a high-performance marine coating. Conventional anti-fouling coatings leech biocides such as copper salts and zinc to kill off fouling organisms and maintain a clean hull.2 Since 2008, the IMO has banned the use of organotin-based ablative coatings due to their detrimental effects on non-target marine organisms.3 The Soft Foul Release (SFR) polymeric coatings are now being widely implemented as an alternative to the ablative technologies, as limited marine life can adhere to the SFR surfaces due to their smoothness, slip, chemical amphiphilicity and gradual release of F-organo oils.4 The newly emerging Hard Foul Release (HFR) coatings are an environmentally friendly alternative to the conventional toxic antifouling and SFR paints — they eliminate the need for biocides, fluoropolymers and silicone oil release.

The HFR’s anti-fouling mechanism resembles that of the SFR coatings, the difference being their improved mechanical endurance, ease of repair and absence of substances detrimental to the aquatic environment, as compared to the SFR technologies. As in the case of the SFR paints, the HFR coatings are expected to reduce the vessels’ drag and carbon footprint as well as lower the underwater radiated noise (URN) levels by reducing the propeller and engine load at constant speed.5

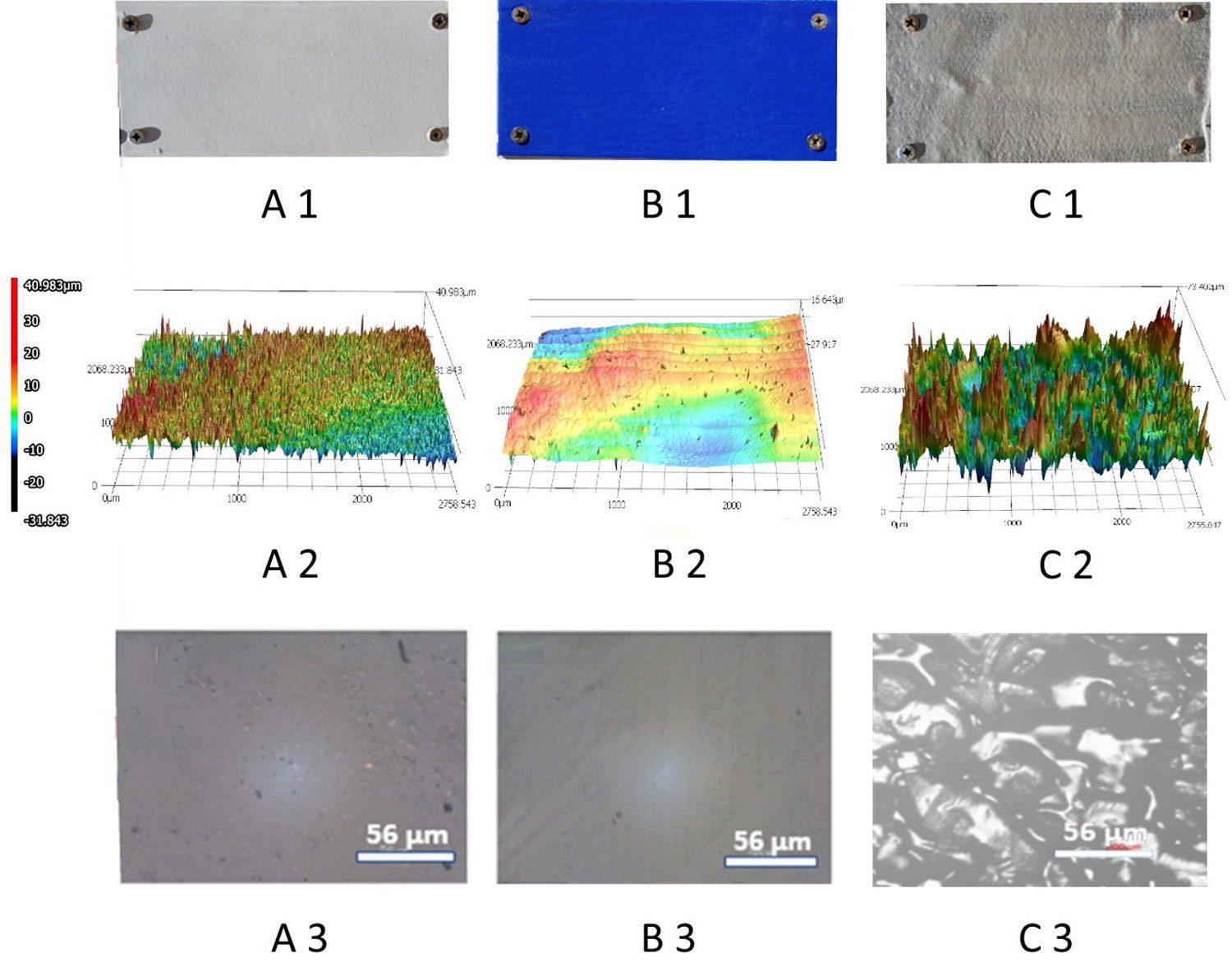

FIGURE 1 ǀ Surface appearances of (A1) HFR product XGIT FUEL (Graphite Innovation and Technologies), (B1) SFR Intersleek 1100SR (AkzoNobel International), and (C1) a heavy-duty cleanable coating, Ecospeed (Subsea Industries); surface submicron-topologies of (A2) XGIT FUEL (B2) Intersleek 1100SR and (C2) Ecospeed through laser confocal microscopy (KEYENCE VK-X1000 confocal scanning laser microscope, Japan); surface micro-structures of (A3) XGIT FUEL, (B3) Intersleek 1100SR and (C3) Ecospeed, through optical microscopy (OMAX 035140U3, USA).

Graphite Innovation and Technologies Inc. (GIT) has recently patented6 the HFR technology, which is based on the interplay between the self-assembly of polymeric blends upon spraying and the cross-linking mechanism, and combined the amphiphilic polymers with graphene nano-pigments, which upon thermo-reactive curing, obtained the rigid amphiphilic finish, capable of suppressing the adhesive interaction with the fouling species.

On the micron level, as shown by the optical microscopy, both the SFR and HFR coatings appeared equally smooth (Figure 1, A3 and B3). On the submicron scale, the SFR coating had the smoothest finish of the two, with average roughness (Ra) of 0.31 μm, and only occasional surface artefacts as seen from the confocal images (Figure 1, B2), compared to about 1.5 μm Ra detected for the HFR coating. Micro-topography of the hard cleanable coating Ecospeed had the highest average peak heights (Sa) of ca. 5 μm and maximum peak heights (Sz) of about 70 μm, almost five times that of the SFR and HFR systems, which as discussed further, could be causative to the hydrodynamic drag penalties and suggested high biofouling attachment rates. The XGIT Fuel HFR product revealed a relatively patterned finish, comparable to that of the 1100SR, with a consistent dense sub-micron topology, consisting of the peaks with pointed geometry, as characterized by the highest arithmetic surface curvature (Spc) of about 530 mm-1 (Figure 1, A2). As shown by the ocean tests below, the foul-release performance of both model coatings could not be directly attributed to the topcoat’s morphology. The benefit of the submicronically patterned finish for the anti-fouling properties of the HFR systems is up for debate based on the upcoming research.

Hull Cleaning and Propeller Polishing Activities

An active method to maintain a ship’s best operational fuel consumption and lower its carbon emissions is to keep the hull and the propeller clean from biofouling. Biofouling growth on a ship’s underwater hull area can increase the frictional drag resistance by greater than 100%, and the resulting fuel consumption by greater than 40%, depending on ther flow regime and resulting Froude number.7 Underwater hull and propeller cleaning techniques can restore the clean profile of the surface; however, they can also generate other issues:

- Previous studies demonstrated that some hull cleaning techniques can significantly increase biocide emissions, namely copper compounds, from recreational vessels.8, 9

- In the case of biocide-free coatings, such as silicone-based SFRs, the coating can be damaged if cleaned due to its low mechanical strength. Also, biocide-based coatings will increase the roughness of a ship’s hull over time.

- Both silicone-based SFRs and biocide-based coatings reduce their performance after underwater cleaning due to biocide depletion (copper or silicone oils).

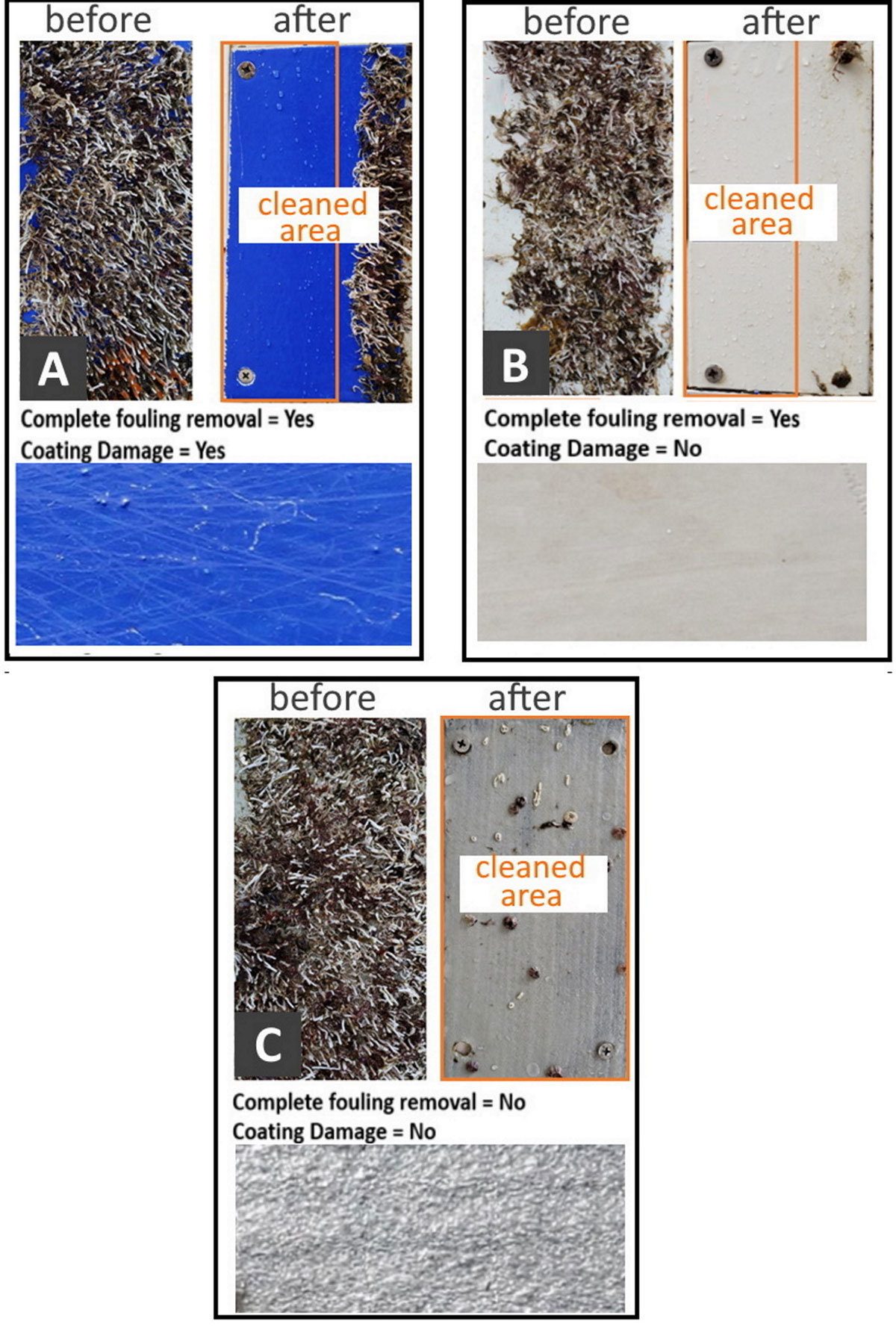

FIGURE 2 ǀ Visual comparison of the three tested systems at various stages of the biofouling and grooming study: (A) Intersleek 1100SR (SFR coating) — Blue panel, (B) XGIT Fuel (HFR coating) — white panel, (C) Ecospeed (inert cleanable coating) — grey panel. In each one of the three sections of the figure, the left specimen depicts the panel pre-grooming, the panel to the right represent the surface area cleaned by the roboticized nylon brush (outlined in orange), and the lower image represents a photograph of the coating’s finish post-grooming.

Biofouling Performance

The antifouling properties and durability of an HFR coating help maintain an undisturbed hull throughout a vessel’s lifecycle, which includes both the shear-induced fouling self-release upon the ship’s propulsion, and the soft grooming procedures. The mechanical grooming of vessels (habitual and frequent mechanical maintenance of submerged ship hulls with minimal impact to the coating) while in port has been proposed as a viable method to control biofouling growth.10, 11

GIT has partnered with the group of Prof. G. Swain (Center for Corrosion and Biofouling Control) to quantify static fouling of the XGIT FUEL hard amphiphile product, and to validate the in-water grooming12 to quantify efforts on maintaining the coatings free of fouling and to compare with commercial “inert” industry standards: non-toxic cleanable coating Ecospeed, and the SFR system IS1100SR — excellent for foul-release performance and known for its mechanical setbacks. The three outlined paints were coated onto three 4-by-8” sand-blasted mild steel plates, immersed in the ocean water in Port Canaveral, Florida for 5 weeks (July, 2021), followed by the assessment of their foul-release potential.

The images in Figure 2 show the comparison between three coatings after being kept stationary for 5 weeks. Soft and calcareous fouling consisting of mainly tubeworms was present on all surfaces at a minimum of 30% surface coverage. Barnacles were present on all surfaces, and for IS1100SR and XGIT Fuel, were present as partially grazed (broken by fish) organisms. All coatings were subject to grooming using a commercial nylon hull cleaning brush, which ran four passes along the tested topcoats. The only surface to fully clean without any damage was XGIT-Fuel. This coating was also not fully exposed to the brush, yet all hard fouling removed by dynamics adjacent to the bush (Figure 2: B), indicating very low fouling adhesion, and thus, a strong foul-releasing performance. Visual comparison of the groomed coatings did not reveal significant damaging of either Ecospeed or XGIT Fuel products, while Intersleek 1100SR developed scratches and grooves, which most likely resulted from the calcareous debris generated in the course of the mechanical cleaning, practically confirming the in-field mechanical robustness of the HFR approach.

EEXI — Quantifying Shipping Efficiency

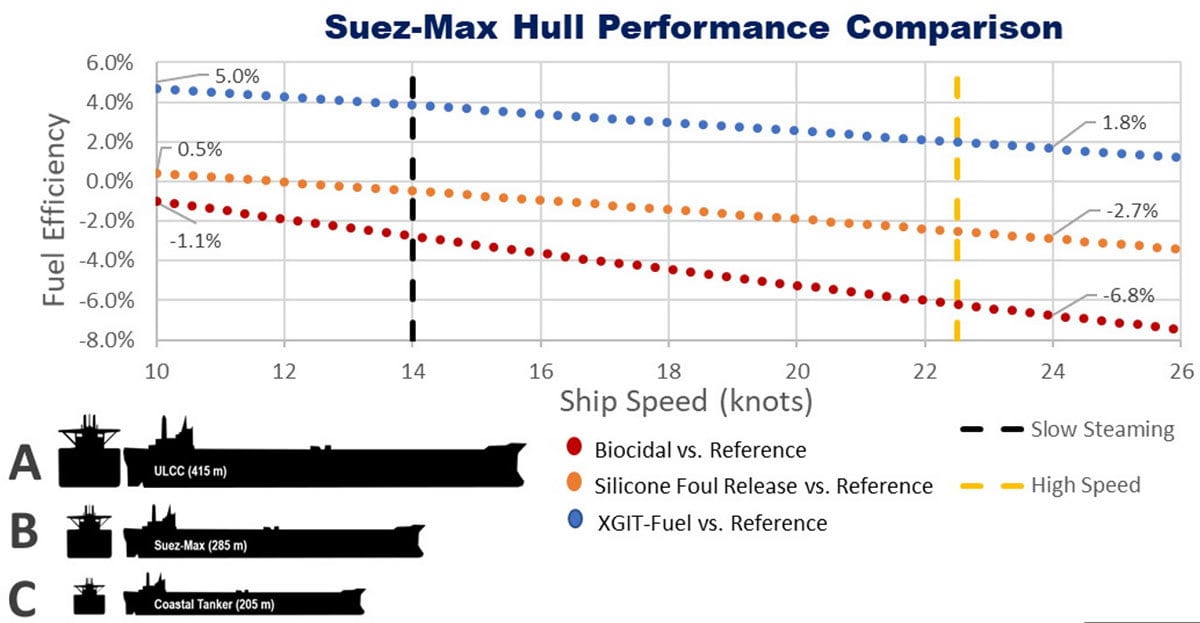

Biofouling of the ship’s hull leads to an increase of its skin friction, hence, frictional drag penalties and fuel consumption, which translates to a higher GHG footprint. Another factor that influences drag is the hull roughness when a coating is first applied and throughout the duration of a drydock cycle. A smooth, low-friction coating such as XGIT-Fuel can provide fuel savings when it is first applied (depending on how long they can maintain a clean surface) and throughout the drydock cycle due to its inert surface and increased durability. Eastern Pacific Shipping’s vessel Kent, a 180-m LPG tanker vessel whose operating speed varies between 10-16 knots, can achieve an approximate fuel savings of 6%-12% with XGIT-Fuel compared to a biocide-based antifouling or an icebreaking coating due to less frictional forces (predictions shown in Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 ǀ Fuel savings projections for Quebec, a 180-m LPG tanker vessel (pictured above) with various types of freshly applied marine coatings (HFR, SFR, Copper Biocide AF and icebreaking). Fuel efficiency based on friction resistance over a range of Reynolds numbers.

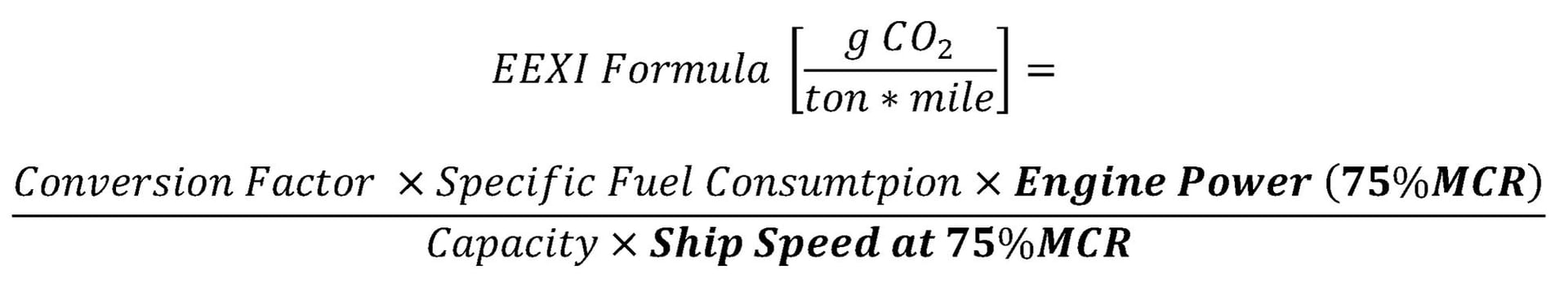

The EEXI formula for ships contains a fixed Engine Power value at 75% of the Maximum Continuous Rating (MCR). Therefore, any fuel efficiency benefit is realized as an increase in speed at constant power in the EEXI calculation, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1 ǀ Fuel efficiency benefits as realized with the EEXI calculation.

Depending on the original coating system, changing the topcoat to XGIT-Fuel can improve a ship’s EEXI by 0.5% — 3.9%, which helps ship owners meet their EEXI and CII reduction objectives and improves their bottom line.

Conclusions

GIT has developed and specifically tailored the specialty topcoat’s HFR and durability properties to reduce the hard fouling, which was modelled to cut the hydrodynamic drag and fuel consumption of coated vessels. These performance benefits are forecasted to improve a ship’s EEXI, utilizing the HFR topcoat, by up to 3.7%.

A smooth underwater hull surface can improve a ship's energy efficiency by reducing the ship's frictional resistance and propeller load. This effect will also aid in the reduction of underwater noise emanating from the ship. Effective hull coatings that reduce drag can facilitate the reduction of underwater noise as well as improve fuel efficiency and reduce GHG emissions.

For more information, e-mail marcielgaier@grapheneenterprise.ca.

Acknowledgements

MASc Mehedi Hasan, Clayton Galvan (Graphite Innovation and Technologies, NS Canada) — for outstanding help with the coating’s physical-chemical characterization. Prof. Geoffrey Swain, Melissa Tribou (Center for Corrosion and Biofouling control, FL, USA) — for help with the ocean tests. Prof. Kevin Plucknett, Dr. Mark Yao Amegadzie, (Dalhousie University, NS, Canada) — for the confocal imaging.

References

1 IMO, “Further shipping GHG emission reduction measures adopted,” 2021. https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/pages/MEPC76.aspx (accessed Jan. 10, 2022).

2 Schultz, M.P. Effects of Coating Roughness and Biofouling on Ship Resistance and Powering, Biofouling, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 331-341, Oct. 2007, doi: 10.1080/08927010701461974.

3 Dafforn, K.A.; Lewis, J.A.; Johnston, E.L. Antifouling Strategies: History and Regulation, Ecological Impacts and Mitigation, Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 453-465, Mar. 2011, doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2011.01.012.

4 Zhang, Z.P.; Qi, Y.H.; Ba, M.; Liu, F. Investigation of Silicone Oil Leaching in PDMS Fouling Release Coating by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope, Adv. Mater. Res., vol. 842, pp. 737–741, 2014, doi: 10.4028/WWW.SCIENTIFIC.NET/AMR.842.737.

5 Vard Marine Inc., “SHIP UNDERWATER RADIATED NOISE,” 2019. Accessed: Jan. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/tc/T29-151-2019-eng.pdf.

6 Gaier,M.; AlGermozi, M.; Rodionov, I. Composition for a Coating. Coatings and Methods Thereof, Internation Patent WO2021/226699 A1, Graphite Innovation and Technologies Inc., May 2021.

7 Demirel, Y.K.; Song, S.; Turan, O.; Incecik, A. Practical Added Resistance Diagrams to Predict Fouling Impact on Ship Performance,” Ocean Eng., vol. 186, p. 106112, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.106112.

8 Schiff, K.; Diehl, D.; Valkirs, A. Copper Emissions from Antifouling Paint on Recreational Vessels,” Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 48, no. 3–4, pp. 371-377, 2004,